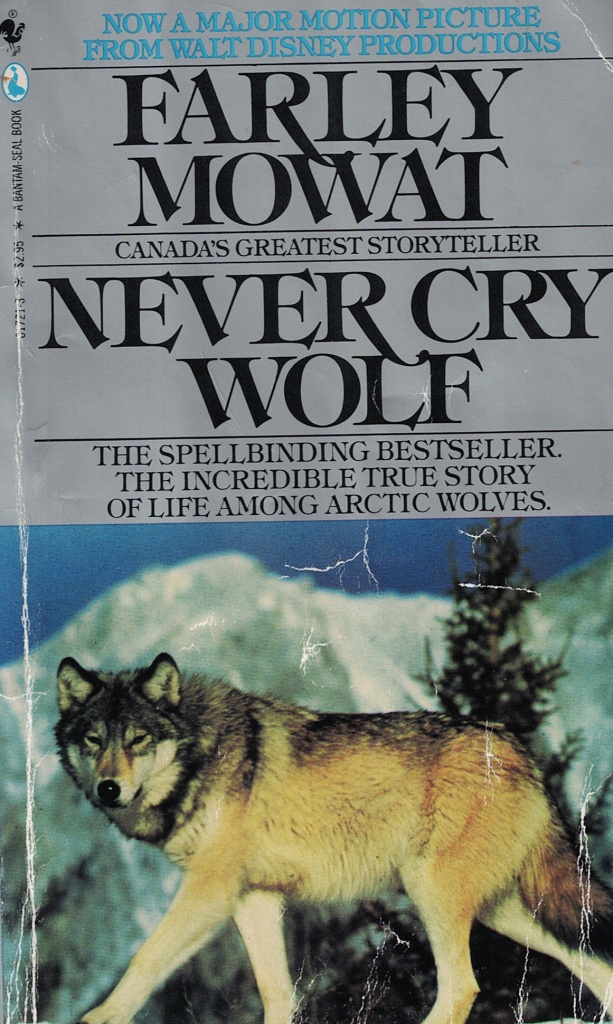

I recently ordered this well-thumbed paperback book, suitably enough, from a bookstore in Victoria, B.C., where I grew up. During my 1983/84 Grade Six school year at Willows Elementary, these paperbacks were everywhere: on desks, in desks, under desks, in the hallway, on dusty schoolroom floors and I even spotted one being used as a doorstop. It was the book our class was reading at the time and if I’d been less honest I would have made off with a copy, as I really enjoyed the book. I would have even taken home the one holding open the classroom door.

While writing Capturing the Summit, I’ve sometimes thought of this story. Mowat’s charming tale of his studies of wolves in Keewatin Territory, employed by the Canadian government, who had the biased viewpoint that wolves were indiscriminately slaughtering caribou, leaving next to nothing for trappers and hunters.

Three aspects of Mowat’s book jump to mind, and still stuck with me after a recent read, thirty-nine years after Grade Six. Mowat’s tongue-in-cheek writing style makes for a fun read, in what could be a very dry scientific book. His ability to contrast the bureaucracy in Ottawa with the harsh reality of the natural world adds to the humourous background of the situation where he finds himself in the inhospitable north. But what I remember most, beyond his observations of George, Angeline, Uncle Albert and the cubs, are the relationships with the Inuit he makes while doing his work, and his eventual reliance on the traditional knowledge of Mike and, especially, Ootek. It’s an especially grand tale, even though it is brief at 164 pages, giving the reader a sense of what it must be like to study the natural world, and eventually, find yourself a part of it, with all your faults on your head.