This is where you’ll find some of my latest published writing, either in pdf format or the text of the article itself…

Chasing Unfinished Business: The Road to Holberg

(Canadian Biker, September 2015)

It was when Mike Whitfield and I rode past the 50th parallel marker in Campbell River that we knew we were passing into a less explored part of Vancouver Island. There were fewer amenities ahead. Mike was on his F650GS. I rode my Kawasaki KLR650. We thumped along into the compound to be first in line in the waiting lanes for the Quadra Island ferry. Hopping off the bikes, the sea breeze was welcome as we removed our helmets. A whiff of low-tide driftwood and kelp was in the air.

It was the first day of a three-day late Spring adventure into northwestern Vancouver Island. I remembered a friend who lived on Quadra, someone I’d teamed up with in a Vancouver Island rally called the Orca Run two years earlier. Brent Henry was planning a two-month sortie into Australia on a KLR650 and, although trip preparation prevented him from coming with us, he invited us to spend the night at his place. It was bound to be an interesting evening.

After riding off the ferry slowly behind the impressive number of foot passengers walking off at Quathiaski Cove, we met up with Brent at the local plaza and he showed us the way to his castle. Brent’s home was a peaceful place, a modified trailer, tucked into a grassy clearing a short distance from the south shore of the island. A KLR650 on a centre-stand and a Suzuki DL1000 were sheltered under a carport.

Once we settled in, Brent mentioned how generous and helpful Australians are. Through various online adventure rider forums, Brent had been able to secure a Kawasaki KLR650, the bike he knows best, in Australia, through a supportive contact. A variety of hosts would be providing couches and beds for him as he makes his way from Melbourne to Perth. Brent had traveled all over North America on his KLR, most recently out to Prudhoe Bay, Alaska on the Dalton Highway. Along with his riding pals Dave Williams and Jim Martin (who hosts and produces Adventure Rider Radio just down the road from Brent’s place), he had gotten to know the backroads of Vancouver Island thoroughly, making my Vancouver Island off-road travels look like those of a novice.

Next day, with a wave, Mike and I crunched our way down Brent’s gravel driveway and onto the road to the ferry terminal. After the scenic crossing, we focused on the task ahead, getting to Port Hardy. It was 240 kilometres away. Then we’d travel 50 kilometres off-road to the community of Holberg. From there we hoped to get to the northwest tip of Vancouver Island achievable by road: Cape Scott Provincial Park, at the trailhead for the hike to San Josef Bay.

After riding the steep ramp off the Powell River Queen, the change was almost instant. There was a climb and the air got distinctly colder. The road no longer followed the sea. It took us west, sometimes even southwest, away from the salt air of Discovery Passage and Johnstone Strait. The rise continued and soon I was pulling over to a rest stop and digging in my panniers for my heated vest.

I grew up on Vancouver Island, in Victoria. Its creature comforts were far removed from the rugged country we were climbing into, yet somehow part of this same island. Seven years before, going through a difficult separation, I had hopped onto my KLR650 and had ridden north solo, hoping to find answers in the northern recesses of the island I called home. Instead of finding answers, I had become more puzzled. How did I place this craggy, yet stunning, place of towering mountains, vast stands of cedar and hemlock and few human beings on the Vancouver Island I thought I knew?

On that trip seven years ago, I had ridden into Port Hardy and had considered taking the gravel road to the northwest tip of the island, just to say I had. But I didn’t do it. I had stayed at a hotel in Port Hardy watching dozens of eagles rip leftover salmon from a trawler to shreds, the birds of prey swooping and gliding with joy from their newfound feast. While watching them, I had wondered what was down that road. What had I missed?

With unfinished business like that, you might say I was in a hurry to try the road this time around. Also, three days isn’t a lot to cover 1100 kilometres, getting up the island, then back down to a ferry terminal to return to Vancouver. If anything, we were pushing it. It was time to get a move on. As we punched up the throttles to 120 kilometres per hour, Mike and I made our way to Sayward to fuel up, the increasingly dense stands of coniferous trees almost seeming to crowd us in.

The North Island Route was an unfettered twisty turn festival. The road was quite good and the ride featured long undulating curves with few interruptions. There certainly weren’t any traffic lights! But it was a different climate than in the southern island, and the weather and temperature could change quickly.

Passing the turnoffs for Woss and Port McNeill, the route finally returned from its inland mountainous theme and joined up again with the coast. It covered ground parallel to Queen Charlotte Strait. There were many options from that point. There was a secondary road leading to Port Alice. Or there was the tri-ferry route starting from Port McNeill to the Kwakwaka”wakw village of Alert Bay on Cormorant Island, then the former Finnish settlement of Sointula on Malcolm Island across Broughton Strait.

But Mike and I were pushing on to Port Hardy, where we planned to have lunch after a quick look around. Finding some fish and chips at Captain Hardy’s, we texted our loved ones that we would be out of cell phone range for twenty-four hours. Then we got back on our bikes to take the Holberg Road.

I had mixed feelings as we took the left onto the road. I knew I was dealing with that unfinished business so there was some satisfaction there, but I knew it would not be an easy road. The initial two kilometres were paved. Then the dry, dusty gravel began. It would continue for 50 kilometres. Some rain splattered against my bug-smeared windshield, but quickly stopped.

As I got up on my pegs to redistribute my weight over the front wheel, I looked for the right line to take through the gravel. Luckily, the road is well graded and there were few potholes, but the sections of deep gravel and occasional obstructive stone sticking out of the surface kept my eyes focused on the road ahead. There was one stop along the road I had to make, and was soon hammering on my front brakes, to the bewilderment of Mike behind me.

The Shoe Tree is one of those remarkable points of interest along an unremarkable stretch of gravel road. Back in 1988, a Holberg resident was bored of the drab surroundings on her commute into Port Hardy for groceries and appointments. So she found a tall cedar snag, she nailed her son’s used sneakers to it and the Shoe Tree soon became a success. Over a quarter of a century later it was hard to see a part of the massive trunk available for another pair of tired soles.

The scenery became more interesting as Nahwitti Lake appeared on the right, but I had to remember to keep my focus on the bumpy road ahead, which was now presenting some impressive washboard surfacing, and not leer at the beautiful landscape. The KLR jolted and squeaked, taking a pounding. Just a few kilometres past the junction with Hushamu Main, the road narrowed and several one-lane wood bridges appeared. I loved crossing them, after making sure there were no logging trucks on the other side looking to cross over first. I brake for logging trucks.

The descent into Holberg was quite dramatic, with a few twists requiring attention be paid to speed. Soon some asphalt appeared and the Holberg Store, also the local bed & breakfast, emerged suddenly on the right. We hauled on the brakes, Mike and I, and were soon covering the town’s lone fuel pump in our dust.

All in all the road was typical of gravel roads maintained by logging companies, reminding me of the roads into Carmanah Walbran Provincial Park and Bamfield further south on Vancouver Island.

After dismounting the bikes, checking in with our hosts and changing clothes, we realized we wouldn’t have the time to get out to Cape Scott and return. Disappointment turned to excitement as we realized where we were. We set out instead to explore the town. A sign pointed us to the “suburbs” which consisted of a one-kilometre loop of 1940s era houses, some seemingly empty and dilapidated, others recently maintained with siding or woodwork, several of which have trucks parked in driveways with the WFP logo on the doors. A big employer in Holberg is Western Forest Products.

We crunched down the hill into the town in our hiking boots, spying the marshland of the end of Holberg Inlet. The water of the 70-kilometre inlet began a kilometre away. A log dump and crane were visible in the distance. There were also a surprising number of wood pilings sticking out of the eastern shore of the inlet, the remains of the supports of what was the world’s largest floating town. After a wander through the WFP compound (where all buildings must be covered in beige aluminum siding apparently) and admiring the post office building with a tsunami warning sign, we proceeded to The Scarlet Ibis for a drink.

Whilst enjoying the view of the inlet and the quiet from the patio, our young waitress came out to have a chat. She informed us she was up at 3am that morning splitting cedar shingles at a logging camp near Macjack Main just west of us. Mike and I were impressed, but as we told her of our travels and origin in Vancouver she began talking quickly in the vocabulary of the logger, seemingly glad to have an outsider to talk to. Terms like “B-Train” and “slides” made me realize we had ridden to a part of the island very different than south of the 50th parallel. Up here, people had to diversify and live by their wits. She hinted that there were not many men who tolerated a woman working in the camps. She had to prove herself even harder in the dangerous, highly skilled and male-dominated world of logging on northern Vancouver Island. I listened to her, fascinated by her experience.

A short walk back up the hill to the Holberg B&B was soon followed by dinner in the lovely Hasjka kitchen. Eastern European cooking would fortify us after our 300-kilometre day, 50 of that off-road. Stuffed peppers, meatballs, garlic noodle soup and dumplings soon had us feeling quite satisfied. Mike and I were joined by Milo and Eva Hasjka, their daughter Monika, along with two friendly gentlemen, Keith and David. They were lodgers at the B&B, joking around with the Hasjka clan as though they had been there for weeks. They were technicians working on the radar towers at the nearby station. Holberg used to host a Royal Canadian Air Force base. CFS Holberg closed in 1990, but there are still a few radar towers as part of Canadian Coastal Radar facilities. David, a young fellow with a weathered ball cap and a few days growth on his chin, explored the local beaches when he had time off. He told us it was amazing what could be found washed up on the beach. From brand new shoes to bicycles, tires and housing materials of all kinds, he had found them on this extremity of coastal British Columbia.

Mike and I would pull out of Holberg early the next morning after a pancake breakfast, dealing with the dusty gravel road better in the sun than the cloud and cold of the day before. We would weave our way through the gravel patches and think in our helmets about the peace and the simplicity of this northwestern part of Vancouver Island. Even though the furthest extremity by road had not been reached, there was a smile on my face having connected with another remote part of British Columbia by motorcycle. There could always be, I reminded myself, another trip.

Rider Profile: Don Hatton

Taking on the World

(Motorcycle Mojo, September/October 2015)

by Trevor Marc Hughes

The property at Don Hatton’s ranch is an adventure motorcyclist’s playground. A series of trails have been worn into tall green grass. Hills and valleys undulate through the Cowichan Valley farm. Cows munch unimpressed in a shady corner.

Hatton has led us down a trail with some tight turns, steep descents and sudden climbs on the wet grass. I’m on my KLR650 and three other riders are on DR650s and a lone KTM 1190 Adventure. Traction is hard to find as we follow Hatton on his BMW 1200 GS Adventure. We slip and slide. One rider planning to join a guided motorcycle tour in southern Africa unceremoniously dumps his KTM 1190 when his rear wheel can’t grab any grass. He tumbles down the hill. It takes Hatton, the rider and another student to lift up the big KTM.

“That bike is a pig,” the KTM rider barks in frustration. He’s clearly fatigued and needing a break. Hatton gives him some encouraging words.

I can’t help but think of how many times Don Hatton has had to face this situation, on his own, on much more hostile terrain, in the middle of the piste of the Dakar Rally. As the Canadian with the most international off road rally experience to date, Hatton is in something of a category of his own and ideally suited to be teaching this adventure riding course, which he’s been doing on his ranch since 2007. The three riders and I are his students and have been riding courses and running drills for two hours.

Hatton has competed in the Dakar Rally three times. He has completed the Shamrock Rally of Morocco where he finished fourth, the Abu Dhabi Desert Challenge, the Tunisian Rally, The Sardinian Rally and the Baja 1000 where he finished fourth in his category. The last time he competed in the Dakar Rally, his teammate on the Rally Raid Canada team was Dakar veteran Simon Pavey. He was a member of Cyril Depres’ Factory KTM team when he competed in the Sardinian Rally. He also has got quite a history of motocross racing on Vancouver Island before his international rally career got going at the age of fifty.

We all ride our bikes to the cattle gate, open it up and saunter up the hill to the deck of Hatton’s ranch house on this mildly overcast day. A lovely lunch has been set out on the table overlooking the generous farm property. After enjoying some sandwiches and sipping on some lemonade, Hatton lets slip some news.

“My 2016 Dakar application is in process,” he informs me with a grin.

He has yet to receive the final word, but Don Hatton of Duncan, British Columbia plans to go after the finisher’s medal again, at 57 years of age. But age has never deterred Hatton, only physical setbacks from earlier rally injuries.

“If all goes well,” he says in anticipation, “and my fitness level gets to where I want it to be, we’re going to give it one more shot.”

He now hopes to compose a team under the Rally Raid Canada name and apply and prepare himself to compete in smaller rallies in the meantime.

“Nothing’s final of course until we’ve been accepted. It’s very difficult to get in to the Dakar these days.”

But in raising the funds to compete in such a pricey rally (the basic motorcycle registration fee for the Dakar Rally sits at just over $20,000 CDN), Hatton has found an interesting sponsor…his own local business: Hatton Insurance Agency.

“I happen to know the president. I sleep with the secretary-treasurer,” he jokes, referring to himself and his co-worker wife Natalie, who has been part of his support team in previous rallies, including the Dakar.

You might find that it’s an interesting profession to be in while considering competing in one of the most dangerous races in the world. But for the past two years, Hatton has been building up his Duncan insurance business and he is at the point now where his interest in insurance, motorcycling and rally racing are coming together. Hatton Insurance was awarded a place as one of the top elite insurance brokers in Canada for two years running.

“I’ve been able to take my skills as a motorcyclist and my profession and we’ve created an insurance program for on and off-road motorcycles that’s starting to take off.”

But being able to sponsor other motorcycling events is what Hatton really gets a charge from, helping other start-up events like the Squamish Motorcycle Festival, where he also is a guest speaker and leads a dual sport ride, and the MX101 Yamaha Factory Motocross Team racing in the 2015 Canadian Rockstar Energy Drink Motocross Nationals.

But in as much as things are working out at home, Hatton has a tumultuous relationship with the rally he has dreamt of completing for many years. What bothers him is what he calls the “Dakar Curse”. His previous attempts have met with near-death experiences.

In the 2009 Dakar, Hatton felt he was one hundred percent prepared, but overconfidence and inexperience set him back.

“I went off a jump that I had not seen at 140 km/h,” he admits. “I had some very serious injuries and a lot of broken bones.”

Hatton later learned he had been unconscious on the course for two hours. He would spend seven days in intensive care. He checked himself out of hospital against his doctor’s advice. Hatton believes he has never really recovered from his injuries from that 2009 Dakar experience.

In the 2013 Dakar, Hatton set out, with teammate Simon Pavey, on a prologue, something of a qualifying run where riders were sent on a 13 km sand dune loop, the completion time determining starting order the next day. With a poor finishing time, Hatton started out near the back, closer to the cars and trucks, and far away from his teammate Simon Pavey. A few days later a truck caught up with him in the dunes, wasn’t using its sentinel warning system and plowed into the back of Hatton’s Husqvarna, setting off a chain of events that would end his Dakar only four kilometres away from the end of that day’s stage.

“It is always this snowball effect that leads to disaster in the Dakar,” Hatton sighs. But there’s some more wisdom he’s picked up from previous rallies.

“Except for 2009, the bike I was riding was one that I’d never ridden before,” Hatton confesses. He tells me there were budgetary reasons for this. But there’s a certain amount of trepidation in his voice when he describes the start of the Dakar on a new bike he’s just been introduced to.

“It’s the first time I’ve touched hands on the bike I’m riding,” he says, his hands outstretched as though gripping the bars.

Being on a bike that was like nothing he had ever ridden on the sand before sent him in to the rally unprepared, putting him further behind and nearer the aggressive cars and trucks.

“I was in the middle of them and from then on life was a disaster.”

Add to that a navigation mistake and Hatton was in a nightmare. He compares the sand of Peruvian dunes to talcum powder, and the Husqvarna rally bike a totally different bike than the one he should have been using.

Hatton does believe that Dakar is eighty percent luck, but he’s determined to be more prepared with his physical condition, his team and, most importantly, the bike. He hasn’t decided on which make of motorcycle he’ll be using in 2016, but it will be one that he has been using for training.

He has a plan: to go back to the basics and do what got him Dakar-ready in the first place for 2009.

“I’ve started a new training program and I’m spending a lot more time on my bike riding for fun.”

And part of the fun is sharing what he has to offer with other riders, like he’s doing on this day, preparing them for a ride that will take him along the familiar roads of his own training. Fire roads, forest service roads, trails…the paths that snake through the Cowichan Valley in a complex network. These are Hatton’s training grounds. Although limited in that they don’t match the terrain or environment of Peru, Bolivia or Argentina, they do give Hatton the ability to ride aggressively off-road for an extended period of time and build up his endurance.

“You bring guys in and many times they can’t get around the field and by Day 2 we’re going on some pretty extreme adventure riding. And the smiles on the guys’ faces even though they’re exhausted by the end of it, is worth every minute of it.”

Clearly he enjoys the process of passing along what he’s learned from his international rally experiences to his students. What’s also clear is Hatton also sees himself as a rider on a level field with other riders, and part of a community of riders, someone who is still learning himself, despite his impressive abilities and experiences racing around the world.

“By the end of (this course) they know how to ride properly which means they’re probably not going to get injured. Which is really good for our sport. The less guys that get injured, the less publicity we get the better it is.”

Favorite Ride: North of the Border

(Rider Magazine, July 2015 issue)

by Trevor Marc Hughes

Mount Baker was continuing to be elusive. I was riding my KLR through a cool sunny March day. It presented a great photo opportunity for the inactive volcano in all its snowcapped glory. Just when I cleared another high ridge though, the tree line would appear on the right, blocking my view. I kept the faith, knowing I would get my chance.

I could see a long, undulating ribbon of asphalt in front of my dual sport bike’s windscreen, farm properties to the left, thick mossy forest to my right, as I got up on my foot pegs to clear another long and low speed bump. The speed limit was 50kph and I was in no hurry. The KLR’s potential did seem quite underused, especially in last season’s knobbly tires. The trip certainly could not be categorized as a technical ride, and any other place I wouldn’t recommend it, being straight as an arrow and a well-marked secondary road. But it was interesting in another way, because of where I was riding. I was riding in Canada, but twelve feet to my right was the United States of America.

Zero Avenue follows the 49th parallel north quite closely for about thirty kilometres from Highway 15 at the west until a series of lakes interrupt the road near Abbotsford International Airport. This allowed for a pleasant ride past mainly farmland. As I travelled east, entering the township of Langley, I noticed markers to my right. Short metallic posts buried in a cement foundation stuck out at regular intervals. I pulled the KLR over to the small mossy shoulder to take a picture of one of them. Then, I wondered if I should be doing that.

Having read or been told that there was surveillance equipment and very watchful homeowners along this road, I quickly got my photographs, hopped back on my Kawasaki and continued the adventure. I found a new housing development on the Canada side faced with American swamp on the other and wondered who would choose to live this near to a border, or a swamp.

The noonday sun poked through the treetops and low-lying brush to my right, the occasional ditch presenting the only obstacle in crossing this undefended border. I seemed to be alone on this road and I decided to twist the throttle and accelerate into fourth gear. Not long after I did though, I caught a glimpse of what was unmistakably a U.S. border patrol SUV parked a few metres away on the other side of the border. I instinctively rolled off the throttle. Why was I feeling so nervous?

Just when getting that idyllic photo of Mount Baker was fading from my mind, the road descended, cleared the tree line suddenly and revealed a vast expanse of green farmland, the peaks of Washington State gleaming in the sun and a gust of fresh rural air. It took my breath away. Despite my guilty mind, I was going to stop again on the shoulder for pictures.

Straddling the bike, I unzipped my tank bag to take out the camera once again. Then I heard it, the soft crunch of wheels on gravel right behind me. Uh oh. With one eye closed I turned in my helmet to look in my right mirror. It was a small grey sedan, a lady in her seventies exited, also bringing a camera out of her bag.

“Lovely day,” she said to me as she raised her camera to her eye to take a picture of the landscape ahead. I took a deep breath. I’ve got to relax.

Zero Avenue continued along uninterrupted until the border crossing at Sumas, the open road welcome and my motorcycle happily thumping away in the sun.

Looking for differences in how the land is used on different sides of the border, I saw that on the U.S. side most of the land was privately owned in massive farm estates and large home properties when it wasn’t impenetrable swamp. On the Canadian side there were smaller farm properties, small regional parks with picnic grounds, campgrounds, and winemakers like Township7 on 16th Avenue that have branched off from Okanagan Valley wineries.

The first ride of the season had to come to an end. Reluctantly, I turned around to go back to Vancouver, a forty-five minute ride away. I pointed my front wheel west for the first time that afternoon, quickly getting the bike back into third gear. I realized that this ride might not have been the most technical, twisty, lengthy or varied choice for a first ride of 2014, but it sure got me thinking about other rides. The possibilities, I thought, on either side of this border are endless. Suddenly, my previous paranoia was taken over by a sense of freedom and a desire to ride on, whatever side of the border I chose, as I roared off along the open unbending road.

Hard Call to Make

(Canadian Biker, April 2015 issue)

by Trevor Marc Hughes

As a motorcyclist, I’m a practical guy. My KLR650 didn’t break the bank when I bought it third hand via Craigslist, but I’ve travelled all over British Columbia on it. Equally, when it came time to find the right luggage system for my first multi-week trip into northern B.C. in 2012, I went for practicality, splurging a little bit on 33-litre aluminum panniers and a DIY kit through Happy Trails. On the tail rack, I strapped a waterproof duffel (containing my tent, sleeping bag, clothing and therm-a-rest) using four hardware store bungee cords. This system was economical. And even though it managed to attach my duffel to my dual sport for six thousand kilometres over asphalt and gravel, over two years, in sun and in rain, somewhere between High River and Calgary I lost one of the cords. This put the whole system in doubt. It was no longer practical.

Since then I’ve read the wise words of Chris Scott in my well-thumbed copy of the Adventure Motorcycling Handbook: “…don’t rely solely on elasticated bungees-they will hold something down but not in place so are only good for very light items.” It’s a wonder I didn’t leave my duffel behind in Iskut!

Being in the market for new “kit” can be exciting, but also a little intimidating. There is no shortage of gear one can consider to strap on the back of one’s adventure moto.There are Kreiga, Wolfman, Givi, Happy Trails. There are rear bags, tail bags, enduro duffels. Alternatively there are top boxes, hard cases, soft bags. My head’s spinning already.

I need to figure out what I need the new…item… for. I head out on multi-week trips into the backroads of British Columbia, Washington State and Alberta. Do I need an aluminum top box with a lock that will be securely fastened to the bike? Would a soft luggage option like a removable duffel do?

What works for other riders?

Jose Manzano is a rider I know who goes on multi-week journeys into the US and has owned a BMW R1200GS and currently tours on an S1000R. On the GS, he had a BMW Vario top case, then moved to a Touratech system. The Vario system he seems to have liked best. Easily detachable, not too wide or bulky, it was ideal for motel room stays.

“On the other hand it was very easy to over pack,” he tells me.

For the S1000R, Jose tried the Wolfman Expedition Dry bag, essentially a waterproof vinyl duffel that holds 33 litres, then moved on to the British-made Kreiga US-20 Drybag, a pricier waterproof “universal tailpack system for any motorcycle”. With over thirty years of riding experience on many different makes of bikes, I’m glad to have talked to Jose, but not quite at my decision yet. Plus, his S1000R is a very different bike than my KLR.

Jim Eldridge, Product Specialist at Happy Trails Products, let me know more about what’s popular with tail luggage for the KLR-set planning an adventure.

“From our experience, the most popular tail trunks for the KLR typically fall into the Givi and HTP Aluminum box camps depending on the intended use of the trunk,” he informed me from the Happy Trails HQ in Boise, Idaho.

What about the adventure rider who intends to be out of town for two weeks? What do riders who take their bikes on long backcountry rides favour on the back?

“Where strength and waterproofing are key (riders) tend to go with our aluminum top box in either 43L or even the large 58L size,” Eldridge says. “Those who tend to haul a fair amount of stuff, but ride more weekend single track and tough track back country routes will either stay with the duffel bag and bungee route…or step up a notch to our small and/or large Mojave Soft Tail bag mounted to our T2 plate so they do not have to worry about losing bungee cords.”

Are there advantages to soft luggage or a duffel bag over a hard top box? It would seem so.

“When you have technical up and down sections the aluminum or Givi hard boxes can hit you in the back – sometimes with painful results,” Eldridge concludes.

So for a guy who does on or off road journeys lasting between a weekend and two weeks, I’m getting a sense of what I should get. But I think I’ll ask a few more questions.

Trevor Pavelich is the Sales and Accessory Advisor at Burnaby Kawasaki. He may be able to narrow things down for my make and model.

“There are two buyers out there,” he tells me. “Those that put the hard cases on and those that like the duffel style.”

From the show room, the light glinting off shiny new KLRs, Ninjas and Versys, Pavelich tells me about the many options out there for tail luggage for the KLR650.

“The drag coefficient is something to consider. A bike will handle differently with hard bags,” he says. “At one hundred to one hundred twenty kilometres per hour, the weight balance more to the back, a bike can develop handling issues.”

Another factor is keeping the environment you’re riding through out of your luggage. Dust and water can seep in with nylon bags. So what environment you’re preparing for has to be considered.

“For guys travelling the Dempster Highway in Alaska, it can get dusty. On longer trips nylon bags can let dust in. The kind of dry bag that you can roll the top two or three times keeps it watertight and dust free,” says Pavelich.

Ultimately it is about style and what the individual rider needs. Hard bags are heavier and pricier than a duffel, but they will keep the outside environment outside. But in the case of a drop, there will be more weight to deal with to right the bike.

“Soft luggage can deal with a tip over better than hard luggage, especially if the hard luggage breaks a fastener.”

The other factor is whether you have more than one bike. I don’t have that to consider, but hard bags with specific fasteners wouldn’t be transferable to another bike.

“A soft bag can be transferred from one larger dual sport, like a KLR, to a smaller dual sport for example,” Pavelich concludes.

From his view would seem that Wolfman Expedition Dry duffels and Giant Loop saddlebags are popular choices with a track record.

If the idea of packing a bulky bag, even if it be soft luggage, doesn’t appeal, I found a kind of saddlebag that is molded to the back of a dual sport bike like an extra passenger (albeit much smaller, with fewer appendages). Besides making all kinds of stuff sacks, dry bags and dry pods, Giant Loop makes a waterproof 60-litre bag that clings to the back of the bike and is meant for multi-day adventure rides. It’s also low and is built to reduce bike-handling issues.

Harold Olaf Cecil is the owner and founder of Giant Loop in Bend, Oregon.

“The saddlebags require no special luggage racks,” he says about his kit, pointing out no loops or braces are needed as well. “They simply strap on and off a huge array of makes and models.”

The one he points out to me is the Great Basin, which he says for an “in-between bike” such as the KLR650 “a thumper with a windscreen and body panels”, and with passenger pegs, is a popular choice in his view.

Cecil also points out that, in his experience, hard luggage on the back can be on the weighty side.

“The typical hard luggage system,” he says, “weighs forty plus pounds before you’ve even packed a pair of clean socks.”

He also points out a key worry during a remote adventure. What if your hard luggage bends with a crash? The lids can become misaligned with the boxes. Or what if the solid, but rigid, structure of the boxes transfer so much of a crash’s energy into the subframe of the motorcycle that it causes the bike to fail? Not a good place to be in the backcountry.

“We call our system adventure proof,” Cecil concludes, “because they’re designed to take a beating and not fail in the field…and they keep the bike handling and performing closer to the unpacked bike’s capabilities.”

So, to reiterate, I could go with a hard luggage system for the tail rack of my KLR650, but for my purposes of the multi-day or multi-week adventure, some on and some off road, softer options seem to be more practical. The pros of hard luggage are plenty of room for stuff and solid construction, but the cons are a risk of over-packing, failure in a tip over and possible pain in the backside. It’s also the priciest and most labour-intensive option (if I were to order a DIY kit). I could go with a soft luggage option like a duffel bag. The pros are it’s more affordable at a little over $100 for a basic waterproof duffel and straps. Cons…well there aren’t many. Perhaps the bike would be a little bulkier with a possibility of some top-heavy bike handling performance if packed too ambitiously. Lastly, there’s the adventure proof saddlebag. Pros are that it is designed to minimize bike-handling issues, reduce the possibility of over-packing greatly, and keep the luggage from working against me in a tip-over resulting in damage. The con is the price, with saddlebags from Giant Loop for the KLR650 going for $400 and up.

Hmmm. There’s much to mull over. But is my practical, more economical side winning?

I call up Jose to tell him how my research is going. He is enjoying his Kriega setup for his BMW S1000R. Seeing as how he has sold his other beemer, the R1200GS, he is having an accessories sale to part with the kit he no longer needs from that bike.

He’s parting with his black Wolfman Expedition Dry duffel. He barely used it and he’s asking $100 for it.

So I’ve come full circle. I think I’ve decided.

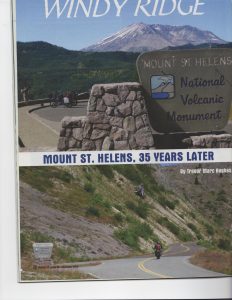

Windy Ridge: 35 years since Mt. St. Helens

(for Inside Motorcycles, December 2014 issue)

by Trevor Marc Hughes

The forest’s shadow suddenly enveloped our motorcycles. The cool was palpable, especially after the heat of the towns of Morton and Randle. There was no other traffic at this early hour, the twists and turns of Forest Service Road 25 a welcome reversal of fortune from the clogged Interstate travel down from British Columbia the day before. The Gifford Pinchot National Forest surrounded us and the freedom of riding this twisty road had me grinning on this sunny morning. This was a big part of why we had travelled to this remote part of Washington State.

Mike and I slowed our motorcycles and crossed the double-yellow line, my Kawasaki KLR650 and his BMW F650GS crunching over gravel, to arrive at a viewpoint overlooking a valley east of us. Getting off my bike and removing my helmet I breathed in the dry forest air and felt the sun on my face. This would be a photo stop, but also our last break before we entered Forest Service Road 99, the road to Windy Ridge. We had read a great deal about the road. There would be switchbacks, it would climb several thousand feet, there would be plenty to distract us so we needed to take care and keep our eyes on the road ahead, there could be wildlife, there would be debris on the road, and there was no guardrail. This stop also had us walking around and preparing ourselves mentally for what we knew was a challenging road ahead.

Nearly 35 years ago the spot where we’d stopped would most likely have been covered in ash, the sky obliterated and day plunged into night. The eruption of Mount St. Helens on the morning of May 18, 1980 was devastating. It began with a punishing avalanche of rock debris, much of one side of the mountain dissolving into nearby Spirit Lake and continuing east. Then a lateral blast wiped out hundreds of square kilometres of old growth forest, flattening trees in some places, killing others where they stood if the root systems were strong enough. A nine-hour eruption featuring thick grey ash covered Eastern Washington and changed air quality for the worse as far north as British Columbia. The pristine landscape surrounding St. Helens was vaporized or laid waste. In 1982, the US government decided to create the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument, a place where nature would be left to follow its course following this destructive event.

This place was where Mike and I would ride to on this warm summer morning.

Forest Service Road 25 continued along in the sheltered forest, climbing twists keeping our speed down to 30 kilometres per hour in some places, the shadows hiding imperfections and sinkholes in the road in others. Then the signage for Forest Service Road 99 shook us from the rhythm of our turns. I took a deep breath. Here we go.

The climb began immediately. This was expected. But what wasn’t expected was the quality of the pavement. After the sinkholes of FSR 25, this road felt like a pool table. The turns were increasingly spectacular and by the time Mike and I surfaced at the first viewpoint, Blast Edge, I think we were both wondering what all the fear mongering was about.

The iconic image of the crater of Mount St. Helens lay before us to the right, a dense growth of new forest carpeted the valley below, some trees shocked to death by the eruption still stood, blanched white. As we dismounted our bikes, I found it hard to imagine I had ridden my KLR from Vancouver, British Columbia, to this place of possibly the most prolific natural disaster of my youth. We instantly lunged for our cameras, as though the crater and surrounding area would disappear soon.

The landscape would change dramatically as we rode on, white tree trunks flattened in the same direction, away from Mt. St. Helens, presented a chilling reminder of the destructive blast. Another one lay ahead. At the Miner’s Car stop lay only the rusting hulk of a car that had been caught up in the blast, the owners killed in a nearby cabin.

The viewpoints continued on, the turns getting more frequent as we did our best to focus on the road, leaning our bikes more and more confidently with each turn. I had read this was a haven for local sport bikers. I could see why.

The hills became increasingly barren, the landscape dotted with new trees and brush. Rock debris from the denuded hills was on the road around every corner, making Mike and I slow down a bit around the blind turns. The roar of our engines reverberated off the passes cut through the rock. We reached Donnybrook Viewpoint, giving us a panoramic view of Spirit Lake. Pulling over and kicking down the stands, we sat in awe of the lake far below where thousands of floating white tree trunks, blasted free of their roots in 1980, lay bobbing like matchsticks in the blue lake. From Donnybrook we could see the looming crater of St. Helens, seemingly flatter now, but only appearing so because we were getting closer to its altitude.

It was with a sense of accomplishment that we rode into the parking lot of Windy Ridge Viewpoint. This was it, the closest our motorcycles could get us to the sleeping volcano. From here the details were visible, the lava dome that had formed over several volcanic events up to 2008 was bulging from the crater, the massive valley stripped of trees and covered in volcanic sludge and the edge of Spirit Lake and its collection of dead tree trunks. Sitting on our bikes, Mike and I could see the outline of the snow-capped mountain that had been, and the ragged edges of the volcanic crater that exists today. But in patches, the greenery of nature was returning to the valley, the shock of the event having worn off. This impressed both of us.

The KLR and GS were coping well with the heat, but without shade Windy Ridge is an unforgiving place on a hot summer day. We drank water. A climb of a few hundred stairs was next as Mike and I left our helmets, gloves and our riding gear at our bikes and started stepping up. Carrying my tank bag with water, maps and cameras up the steps, we finally crested the hill. From there we had an unfettered view of the slope the pumice slid down that fateful day in 1980. Looking down at the parking lot, our motorcycles appearing tiny, dwarfed certainly by the might of the volcano, Mike and I shook our heads in awe of the place we’d ridden to. We were reminded as well about our place in The Ring of Fire as not only were we in view of one volcano, but also visible on the horizon was the pointy peak of Mt. Hood, the rounded dome of Mt. Adams and the massive glaciers of Mt. Rainier, Washington’s tallest peak.

After a quick lunch of packed sandwiches and plenty of fruit juice and water, Mike and I got back on the bikes. Having agreed not to stop until we reached Morton for fuel, this is where the fun began, again. We would ride two of the best motorcycling roads in the Pacific Northwest, FSR 99 and 25, as the early afternoon arrival of plenty more bikers in the Windy Ridge parking lot would attest to. Without anything to distract us, Mike and I took on FSR 99 with the Mt. St. Helens experience in our minds and an enjoyable ride ahead of us.

The advantage of an area stripped of old growth forest is that a motorcyclist can see the twists in the road ahead as well as the imperfections (as there are more sinkholes along the return side of the road and no guardrails to brace a vehicle from falling from a steep slope). But far from being an anxiety-ridden ride, it was one of the most fun I’d experienced. For a forest road, most of which in Canada are covered in gravel, not well engineering and dusty, this was a positive experience.

Plenty of motorcyclists were heading up the s-curves in the opposite direction on the early Saturday afternoon, some on sport bikes taking them aggressively, others on larger touring motorcycles enjoying the twists in a more leisurely way. Most gave us a friendly wave as we plunged back into the welcome shade of the national forest. More twists and turns were in store as we made our way back to Randle and Morton, the protection from the forest canopy cooling us off, our riding gear and helmet vents open to the crisp, cool forest air once again.

A quick fuel-up in Morton had us both stocking up on water. The heat upon stopping was powerful, and we were aware of our need for a hydration break. We continued along US 7, the twists fading but the scenery becoming a lower altitude mix of forests, farms and lakes. Plenty of Harley-Davidson riders were blasting past us. These were bikers that clearly knew these roads like the backs of their hands. Our arrival in Elbe, Washington had us needing a break again. The junction town featured a steam locomotive blowing its whistle before Mike and I whet ours with some fresh strawberry lemonade. We would duck inside converted rail passenger cars, the air-conditioned interior of the Mt. Rainier Railway Dining Co. and talk about our new understanding one of the greatest volcanic events of our time and taking on some of the most enjoyable and fun motorcycling roads in the Pacific Northwest.

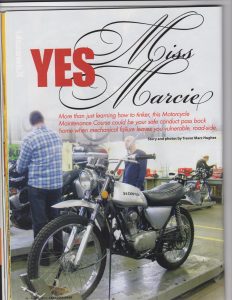

“Yes, Miss Marcie” for Canadian Biker, August 2014 issue

(Originally “More than just tinkering with the bike:

The Motorcycle Maintenance Course”)

By Trevor Marc Hughes

The Suzuki Hayabusa sits at the centre of the room. Our instructor is talking about the aluminum chassis of the high performance sport bike. Only there are some things missing. The 1340cc engine is one. Then there’s the bodywork. And the seat isn’t there either. In fact the ten students surrounding it, including myself, are probably thinking the same thing: It doesn’t look so tough naked.

Marcie has been teaching this course for several terms, has been working as a professional motorcycle mechanic for longer and is patiently explaining why, to a room full of eager motorcyclists with different levels of maintenance experience, the bike needed large disc front brakes along with ABS. This was an intense bike during its lifetime.

But now it’s part of the collection of half-dismantled and “studentized” motorcycles here at the British Columbia Instititue of Technology. BCIT offers this course a few times a year just before the kickoff of the riding season and I’ve been meaning to take it for years.

The class is made up of a wide variety of riders. There’s Angus, the bespectacled British gentleman who is fixing up a Honda CL360. There are two chatty fellows from Israel with a 125cc Honda and a Kawasaki Versys. And then there’s me, the keen student, looking to learn everything from oil & filter changes to tire repair. Essentially I want to know what I can do myself on the road, or off the road, when help is not readily available.

In the night-school classroom we’re presented with breakdowns of two-stroke and four-stroke engines, carburetors, braking systems, electrical systems and handed the innards of motorcycles long dead to touch and see how they function. And we learn about the holy trinity of fuel, compression and spark. If something’s wrong with the motorcycle then it can be usually traced to the trinity. Suck, squeeze, bang blow. It’s catchy and easy to remember. This is not something that will get you arrested, but is what happens in the combustion chamber several times a second.

All this theory and some demos that take us out onto the shop floor are to prepare us for the big event. Saturday Shop Day will take up a whole day. We all seem to be preparing ourselves for it. How do I take full advantage of a shop with everything from digital torque wrenches to a hydraulic workbench? There are so many possibilities as to what we can do to our bikes. There are a few nervous questions about how much work we can get to in six hours.

Marcie passes along some advice about Shop Day: try not to bite off more than you can chew. All bikes that roll in will roll out, even if we go past the scheduled class time.

On Saturday morning at 830am, groggy motorcyclists one-by-one slowly file in under the large roll-up door of the maintenance garage and cut their engines. It’s a rainy day outside and the warm, fluorescent-lit interior of the workshop, covered in colourful Kawasaki and Suzuki posters and banners, is welcome. As we remove our helmets and exchange nonchalant greetings, Marcie greets us with a smile, her fiancé Ian, also a professional mechanic, introducing himself as an assistant for the day.

I’ve got a plan. An oil and filter change on my KLR, cleaning, lubricating and adjusting the chain, followed by a rousing breaking bead session. One of my fears is to be caught in backcountry and have to change a tire. No matter how many videos and demos I’ve watched, I still need to do it myself. And why not do it on Shop Day, when I have a pro looking over my shoulder?

The bikes are loaded onto their individual workbenches, front wheel locked, bikes tied down, the sudden hiss of air from some hinting that they are being raised up. Beck and her Honda Shadow are immediately involved in an oil change behind me. I find an oil pan and get to work.

Next to me, Robbie is studying sockets as he gets to work on the front brake pads on his bright blue Ninja. I open the cover to get at the oil filter, remove it to check the

mounting pin’s bypass valve, and place the filter in the oil pan. I look over at Joe who is seriously working on getting the rear wheel off his scrambler.

Once I’ve inspected the parts, I look for the right socket to remove the drain plug. Since my aftermarket bash plate was put on it’s harder to find, but it’s there, a hole in the plate revealing a shiny bolt. I’ve got to keep something in mind though. I’m the third owner of this KLR. A previous owner did his own oil changes, tightened the plug too much and managed to strip the threads. Kawasaki had to put in a heli-coil kit, which looks like a small spring, but puts in new threads so the drain plug can be screwed back in and hold oil. I’m anticipating a struggle, but I go for it, opening up the plug to let the dark gold 10W40 gush out into the pan. After letting it all drain out, I struggle to find the threads, but get the drain plug back in finger tight before replacing the filter and put the filter cover back on (with the filter in place of course). I fill up with oil and moved on. Check.

As I go into the tool collection to find a digital torque wrench, I hear another student asking to buy some oil as she has poured what she brought through the plug, not having sealed it. I sheepishly pretend not to have heard and bring the wrench case back to my workbench. I find the right socket, plug in the foot/pounds into the reader and righty-tighty the drain plug until it beeps and buzzes. I like it.

The rear wheel lay before me on the carpet, along with three tire irons, a pressure gauge and a core extractor. Looking over my shoulder, the two Israeli fellows are already leaving, having heli-coiled two rearview mirrors into place and tightened some bolts. I can hear the patter of raindrops on the roof high above me. I’m planning on staying late. I remove the cap and core from the tire’s valve stem.

Marcie demonstrates how to get started with breaking the bead closest to me, inserting the first iron in between the rim and the bead, she stands on the iron and moves down a few inches to the right, doing the same thing. It’s not easy, requiring the solo tire changer to have several spare hands. But it can be done with some fancy footwork and shifting of weight. After she has inserted the first trio of irons, she pulls the first one out and hands it to me.

I patiently continue the process, making the best use of my limbs, and back, as I gradually get the wheel off the rim, then carefully reach in to remove the deflated tube. This may not be the side of the highway, but I’m glad to have successfully done this at least once. Now I just have to put it all back together. Keeping track of how the tube fit in the tire, I carefully push the tire back on the rim with the help of some dish soap and water (talcum power, I hear, also works wonders). Then, starting from where the valve stem goes into the rim, I gingerly push the tube back into the tire, sealing it all up with the tire irons in reverse to get the second tire bead onto the rim, doing my best to not pinch the tube with the irons. It’s not as easy as it seems.

Then, the moment of truth, as I see if I didn’t pinch the tube. I refill the tires with air and they inflate and hold air! Wiping some sweat from my work goggles, I breathe a sigh of relief.

Marcie assists me in a quick chain adjustment after I clean and lube the chain. It proves to be a finicky process, as every time I sit on the bike after an adjustment, the chain tenses up tight. After five attempts of loosening the rear wheel axle nut, the chain adjuster locknuts, kicking the rear tire a few times, then tightening the lot and torqueing the axle nut, we finally get it right, only for me to hear Marcie notice another thing.

“I think your suspension’s a bit soft,” she says methodically. Maybe next time?

I stand up and notice something. Everyone has left, not a workbench is occupied. Looking at my watch, I’ve stayed an hour late.

Time flies when you’re having fun.

I’m just glad I didn’t have to replace the engine in that Suzuki Hayabusa in the corner.

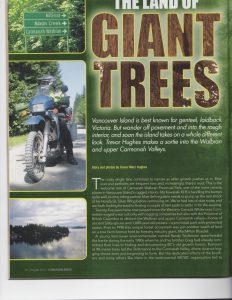

“The Land of Giant Trees” (originally “Carmanah and Bamfield”) for Canadian Biker, August 2014 issue

Carmanah and Bamfield

By Trevor Marc Hughes

The rocky single lane continues to narrow, alder growth pushing us in, bear scat and potholes frequent, and mud becoming increasingly apparent. This is the welcome mat of Carmanah Walbran Provincial Park, needless to say one of the more remote places on the island. But it is remote for a good reason.

My KLR is handling the bumps quite well, but my riding partner, Matt, on his Honda GL Silver Wing, is losing his shock, and regularly needs to pump it up with air before continuing on. We’ve had lots of dust today are both looking forward to finding a couple of tent pads and settling in for the evening.

This place is significant in so many ways. It has been twenty-five years since a battle was fought to preserve the ancient Sitka spruce that call this place home. Prior to 1990 this larger-than-life forest was just another swath of land covered on a tree farm license held by MacMillan Bloedel. A young environmentalist named Randy Stoltman, having heard rumours of trees taller than ninety metres in the Carmanah Valley, found them, along with freshly-cut logging roads and signs they were about to be cut down. After much deliberation in the media, in which I imagine this road we are travelling today being well-worn by journalists and environmentalists alike, Carmanah was made into a provincial park in 1990 to preserve, what many believe, are the oldest trees standing in Canada.

We’re totally alone in the campground, our faces darkened from dust, riding our bikes along a grassy and muddy trail to our site at the far end. Cutting the engines, the silence is deafening once we remove our helmets, followed by the croaks of frogs and the call of a raven. Charged up by the accomplishment of riding the bikes, avoiding potholes and pushing on slowly through the dust all day, we don’t stop there. We push downwards on foot, to hike the trail along Carmanah Creek leading to Heaven Grove and a spot dedicated to Stoltman. Weaving along narrow elevated boardwalks we finally arrive at a collection of thick, deep-green, moss-covered trunks, rising above us at over eighty metres, many centuries old. Awesome is a word overused these days, but the sight of these ancient trees brimming over with life is truly awesome. It’s now getting dark, and we hoof it back to the campsite so we can cook dinner on my tiny camp stove before we can’t find anything.

One of my concerns about this trip was that I wouldn’t be able to find this place. Checking topographical maps and reading accounts of previous travels to Carmanah buoyed me on to believe it was possible. And it is. The roads and junctions were well signposted, and I soon relax into the ride. However, we pass few other travellers. But those we come across, while we stop for a break, are curious about us, and ask if we’re all right.

Next day, after breaking camp, having done another hike to another impressive collection of immense, moss-covered ancients called The Three Sisters, we start the bikes and push on in the bleaching sunlight along the ascending and descending rocky switchbacks of Rosander Main, leaning left to cross the high bridge over the Caycuse River, and back to the wide and well-graded loose gravel roads leading to Nitinat Junction, where we stop as we did the day before. Turn right and we’d return to Lake Cowichan, where we picked up a few groceries yesterday. But our plan is to continue straight on, to try to reach a remote fishing town on the west coast of Vancouver Island called Bamfield. As we stretch our legs, have an energy bar, and Matt pumps up his shock, a vandalized green-and-white direction sign creaks creepily across the road, dangling by one fastener, uselessly pointing travellers in the wrong direction to Bamfield or Carmanah. But Matt and I now know from our maps and some common sense where we’re going. We blast away in a dust cloud from the junction, tires crunching over gravel, leaving the hobbled sign to creak alone.

Another few kilometres and we breeze onto very welcome smooth asphalt. At least it feels smooth after the last hundred kilometres of bone-rattling gravel and rock. It lasts past Francis Lake on the right, a small recreation site visible on the beach through the trees. It lasts past Franklin Camp, a gate denoting a large piece of land reserved for loggers. But it disappears altogether once we veer left onto the Bamfield Road, plunging me into the total focus of keeping the bike at speed through the loose gravel through a particularly unattractive clear-cut section. Segments of trees have been pushed together ungracefully to the left and right, reminding me of what could have happened at Carmanah had people not opposed logging there.

My KLR is on knobbly T63s, but Matt is on fading street Dunlops, and I can tell he is struggling to maintain the bike upright but he does a great job of it. I’m sometimes telling myself to loosen up and take a deep breath, finding myself tensing up over the slippery curves, trusting myself to speed up and letting the gyroscopic effect take over.

There are various options along the Bamfield Road, including a turn into Poett Nook to have a peek at lanky Alberni Inlet, but Matt and I choose to motor on, figuring we’ll have a good view in Bamfield once we reach Pachena Bay.

The exercise of avoiding potholes and standing up on footpegs comes to an end at the incredibly smooth asphalt of Bamfield, and we’re tired. The first thing we come to is the Pacific Rim National Park sign, denoting this as the start of the famous West Coast Trail, one of the biggest draws for visitors to Bamfield. The trail covers seventy-five kilometres between here and Port Renfrew and is very popular. The next sign we see is beautifully done woodwork, also beautiful because it means a short ride to a campsite by the beach. The Huu-ay-aht people run the Pachena Bay Campground and it is one of the best I have ever visited, with all amenities, making all that off-road work worth it.

There’s nothing but Asia out the mouth of Pachena Bay, and tsunami evacuation plans posted around the campground facilities remind visitors of the raw nature of life on the west coast of Vancouver Island. The campsite looks out at the bay and massive caves to the right. Eagles searching for dinner swoop around well-rooted spruce and cedar above us.

Smiling at each other, knowing we’ve once again tackled some difficult terrain, Matt and I set about freeing our one-man tents from our bikes. A pickup truck pulls up and two fellows from the nearby reservation community shoot the breeze with us before offering us fresh crab. Matt and I look at each other, shrug, and decide to boost our camp food supplies with something local. One of the men takes the lid off a large rubber bowl, showing us a dozen clicking and alive-and-kicking crab. We didn’t know they’d be that fresh!

While sitting at the picnic table, my camp stove boiling a crab awkwardly stuffed inside my largest camping pot, Matt and I talk about the network of logging roads, forest service roads, and private gravel roads that sprawl across the fringes of Vancouver Island. There are so many pleasurable destinations such as this to discover, if only we trust in adventure and solitude.

After eating delicious white crab meat washed down with a local beer, Matt and I ride into Bamfield before sunset to take in the sight of the town from the heights occupied by the Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre, a research facility run by several universities including UBC and UVic. As the sun sets over the town of three hundred souls, we both look down from the rails above, listening to the quiet hums of small fishing boats in Trevor Channel, admiring the little marinas across a small inlet on Bamfield’s accessible-only-by-boat west side, and quietly considering the difference a couple of days make in the type of communities to be found on Vancouver Island, if only we go off the beaten path.

“The Hurley to Bralorne” for Canadian Biker, July 2014 issue

By Trevor Marc Hughes

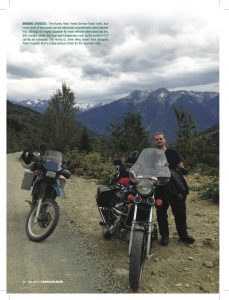

The switchbacks were made of loose rocks and gravel and continued relentlessly upwards. The back wheel of my KLR, sheathed in a Michelin T63 knobbly tire, was all the same slipping out behind me as I struggled to maintain speed. 4×4 trucks were coming down this road, on their way to Pemberton or Whistler maybe, at unexpected times and at great speed, generating clouds of dust. Matt rode his stubborn Honda GL Silver Wing and we were both fighting to find and keep a good line while making nearly one hundred and eighty degree turns up and out of Pemberton Meadows.

After awhile the road straightened and Matt would signal me by flexing his index finger up and down in his gloved hand, our code that a photo opportunity was at hand. Both our bikes bumped to a stop near the steep verge. Before us was a gorgeous vista of the meadows, we had climbed out of, the Lillooet River gushing along, mountains beyond and a steep fall a few feet away.

Matt and I were on our way to the remote community of Bralorne where, in the 1930s and into the forties, the most important gold mines in B.C. were located. At Pioneer Mine, just up the road from the small town, 1933 saw the operation produce over eighty thousand ounces of gold, valued at nearly 2.5 million dollars. And this was at a time when very few were making profits. Mining at Pioneer ceased in 1960 and with the closure of Bralorne mine in 1971, the Bridge River valley communities developed a reputation as ghost towns, even though people continued to live there, enjoying snowmobiling, mountain biking, skiing and hiking. The population may have dropped from thousands to tens, but it still drew adventure and outdoor enthusiasts.

But first, Matt and I had to conquer “The Hurley” a rough and tumble road with an even rougher reputation. There were “I Survived The Hurley” bumper stickers for sale, and I intended to get one! It’s a seasonal gravel road, maintained occasionally, that has limited access by the start of Fall and is closed by November. But it is the quickest route to Bralorne from Vancouver.

Once the switchbacks were managed, there was still the matter of about fifty kilometres of bumpy gravel, large potholes and washboard surface to negotiate. It was about five o’clock, and we both knew we were playing beat the clock on this late September evening, wanting to get to the motel before dark. Riding on The Hurley at night is not recommended.

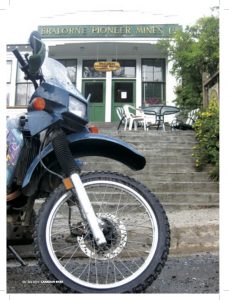

When I had booked a room at the Bralorne Pioneer Motel, visitor accommodation created out of the remnants of the old mine offices, I wasn’t sure what to expect. I spoke with Kathleen on the phone while I removed my credit card from my wallet. She told me, when I arrived, to go into room 1, the room keys would be on the table and to leave forty dollars on the table and the keys when I was done. I thanked her and put down the phone, still clutching my VISA in disbelief. I was clearly going someplace where my big city concerns had no place.

The light was running out when Matt and I found a fork in the road, the fading signs before us pointing out local hotels. Stopping the bikes to consult the topographical map, we knew we had to keep the Hurley River that we had been following on our left, so we took a right. Up on our foot pegs as we bumped along a road that deteriorated to two muddy tracks that passed recently logged hillsides, we eventually found a facility along Cadwallader Creek that was well lit. It was extensive, looking industrial, in a low dip to the left of the last part of the East Hurley Road, the gravel and mud turning to a single lane of asphalt. Little did we know this was the new hope of the community, digging back into the veins of the past, looking for new lodes, the renewed Bralorne Mine which had only recently started up operations again.

As the last light of the cool September day faded, Matt and I crested a hill, meeting the first stop sign in hours. Before us was the main strip of Bralorne, the Mineshaft Pub, the Bralorne Pioneer Motel and the road leading to the Pioneer Mine ruins stretched out in broken concrete before us. We had found our home for the night and I cut the engine and pushed the bike to the curb in front of the old green and white mine office. We had conquered The Hurley and made it into the South Chilcotin Mountains, 3350 feet above sea level, on our trusty motorcycles.

While taking my tank bag and duffel off the KLR while Matt went for an exploratory spin around the town, I found the office’s door-sized safe, the security housing for gold bricks from the mines in days gone by. The motel was quiet, with high ceilings, hard wood floors, long hallways and a big bed and bathroom in my comfy room. The only other sign of activity was a sign for the town’s only coffee shop, Lone Goat Coffee.

The next morning, after my exploratory walk around Bralorne, I met Matt at Lone Goat for a welcome morning espresso and breakfast. We talked to Christine Devereux, who has run the coffee stop with her husband for over two years. She says business has been slow this year but there are “quite a few motorcycle groups…all guys” that visit the town during summer months, taking The Hurley, exploring the local roads, many trails carved out of the wilderness by original mine workers, then exiting via “Road 40” along Carpenter Lake back to the gold rush epicentre of Lillooet.

After a stop at the Bralorne-Pioneer Museum to look at artifacts from the bygone days of mining, Matt and I got on our bikes to continue along loose gravel through to the abandoned town of Bradian, something of a former residential neighbourhood for mining personnel and their families. The homes were now boarded up, with rusted corrugated roofs, dusty and silent. After a few switchbacks, it lay before us; the remnants of Pioneer Mine. Matt and I put down the stands and stepped off the bikes into the past. Although visitors have to use their imaginations, the piles of wood and scrap metal before us next to Cadwallader Creek were the actual materials that helped this community be BC’s top gold producer in the 1930s. Some of the planks of wood would have fortified the original 1916 mill. Just visible in the wreckage were rusted steel rollers that may have ground up tons of ore in a given day.

After picking through the ruins of Pioneer Mine, Matt and I swung the bikes around to visit one of Bralorne’s most vocal supporters. The owner of the building housing the Mineshaft Pub, Bruce Simon, is an avid rider, with a BMW R1200GS and a Harley-Davidson Road King in his garage. When we stopped by, he had just finished having concrete poured for the foundations of a house for his son on his property near Bradian. It’s a sign of the revitalization of the town. Although Bruce will be the first to tell you there’s more to do around Bralorne than pan for gold.

“There are so many good circle routes spreading out from Bralorne,” he tells me, making route maps in the gravel with his work boot. “D’Arcy, Seton Portage, Tyaughton, The Hurley, and Carpenter Lake Road, they all create these great loops that are perfect for an adventure on a motorcycle.”

Bruce came from Langley, B.C. originally and visited Bralorne for the first time with family a few years ago. He liked the area so much a few weeks later he found himself the owner of the local watering hole and a house.

After shooting the breeze with Bruce and his two construction buddies, Brian and Scotty, Matt and I were off to ride part of one of Bruce’s recommended routes, the Carpenter Lake Road or Route 40 to get us back to Lillooet.

We left town along a well-paved road, the downhill twisties really enjoyable as we passed beautiful views of Mount Sloan and Downton Lake and the lone purple house of the old mining community of Brexton before reaching the larger town of Gold Bridge.

The bridge got us to the north shore of Carpenter Lake, onto a road that would last 106 kilometres of mostly paved road, weaving excitingly along the emerald green of the massive lake, the big peaks of the Bendor Range on the far shore to our right. The hugely enjoyable scenic riding would take us for hours along twisty roads ending in the dry gorges near Lillooet, bringing us up along the slow turns of switchbacks to ascend to the arid landscape of Canada’s hottest environment, then the descent into Lillooet, where all golden paths began.

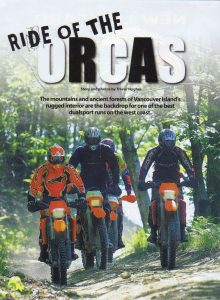

“Ride of the Orcas” for Canadian Biker, March 2014 issue

Orca Run 2013

The rain fell in heaps now that I was on Highway 18, firmly committed to my first off-road rally. It was a cold May day as it was and I was wearing my liners and heated vest, but a bit of me was still getting wet. The KLR was fully loaded, aluminum panniers carrying enough camping gear and food for two days and nights. The duffel bag was lashed to the rack with my trusty one-man tent, sleeping bag and Therm-A-Rest.

I had heard much about the Orca Run. Some of it was from forums online and some of it was from talking to other bikers while in a ferry lineup coming back from a day’s riding on Vancouver Island. I had heard it was a fun gathering of adventure-minded bikers from across the island bringing with them KLRs, KTMs, Husqvarnas and any and all dual sport bikes and bikers up for a challenge.

I knew in past years there were three routes of varying degree of challenge, designated A, B and C. The As were the toughest…single-track, river-crossings, snow and ice on higher elevations, that kind of thing. C routes were along scenic forest service roads. I had been told by the organizers of the 2013 event, held in the beautiful Cowichan Valley, that the event was downsized this year and would feature only C routes.

But while riding Highway 18, the rain kept me from seeing any of the beautiful Cowichan Valley. It was only when getting under the canopy of the forest at Gordon Bay Provincial Park, my home for the weekend, that I could see a little bit of it.

The group campsite featured a shelter building, a wood-burning stove poking a chimney out the roof, a clearing for pitching tents, and a few early arrivals on this day before the event including seriously modified KLRs, BMWs and a KTM or two. Putting down my stand near them, I walked over to a registration tent to get my T-shirt and instructions. It was time to pitch my tent before the rain started up again.

After a few hours sleep, I woke up to the pitter-patter of raindrops on my tent. Emerging to hastily put on riding boots and cook a quick breakfast on my pocket stove, I soon joined in on a rider’s meeting. It was 8am.

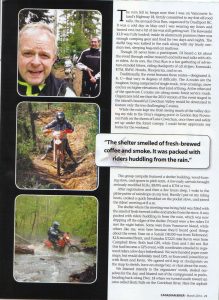

The rider’s meeting in the shelter building was filled with the smell of fresh-brewed coffee and smoke from the stove. It was packed with riders huddling in from the rain, which was now dripping off the edges of the shelter. Present were a few riders I’d met the night before, some from Vancouver Island, some, like me, who had heard good things about the event, had ventured over on the ferry to try it out. One was Eran from Richmond, on a Suzuki DR350. Two more, I would hastily meet before agreeing to ride together were Brent on his KLR from Campbell River and Kevin on his kickstarted Yamaha XT225. Brent and Kevin had GPS, Eran and I did not. This had become a GPS event, with coordinates emailed to registered riders a few days beforehand. We were handed paper route maps, but would need GPS. We listened to the organizers words in complete silence and seriousness, steeling ourselves for anything the day would throw at us.

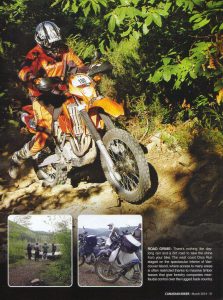

We would blast out of the campground in packs, heading out back along Highway 18 to turn south towards Skutz Falls. It was around here the asphalt dwindled to become potholed mud and gravel. Time to get up on the pegs.

We had agreed as a group to stop at checkpoints on the map. As it turned out so had many of the other riders, and these were places to stretch, sometimes have an energy bar, or to chat about the route. The rain continued to fall lightly as we passed actively logged areas, stumps, big potholes and debris scattered along the road. At first, I tried to avoid potholes, then they became so many that it was a matter of damage control—whichever potholes I disliked the least I would take on, splash through, and trust in KLR. There were some slippery muddy sections and soon we would be making an ascent to Lois Lake through a recently cleared single track, what other riders called a “thread the needle” section. It was called that because a rider had just enough room to clear a passing branch, dip into a rut, avoid another branch, run over a small tree that had fallen in the winter, and do it all over again. It was exciting. I loved it. But you couldn’t look away for a second. That lasted for about a half-hour before a rest stop.

The next section would push us to lunch break at Wild Deer Lake, an extremely rutted narrow bit that would also keep me on my toes as I geared up, then geared down, ducked and weaved to avoid more heavy foliage, and where the terrain got increasingly rocky. This was a road few people used. On the map was a “bail from Wild Deer” route the organizers told us about at the riders meeting, a road you could take if injured or the bike had broken down. So far so good, though. I was having fun.

We could speed up along Stoltz Main, a well-graded and wide road, lumber company signage pointing the way. This would lead us to a few scenic spots, including Pete’s Pond, a local spot to camp and fish, incredibly pristine and beautiful, where Brent, Eran, Kevin, and I admired the collection of wet clay gathering on our machines. Kevin would etch a Canada flag on his license plate with his gloved finger.

The final section would prove to be challenging for me. On a rocky ascent overlooking a beautiful valley, the rain falling lightly, a narrow slippery track would get the better of me, the KLR and I falling to the left, the wheel spinning out and spitting out stones the size of my fist. The left was better than the right, which led the way to a steep fall into the valley. Getting up, wiping leaking fuel from the top of my tank, my new friends helping me get the bike upright, I would do the same twice before letting go of the clutch, staying in first gear and conquering the steep ascent. I was lucky, neither my bike or myself were damaged.

The view from the top was all the more rewarding for having done what I did, and working as a team to all get there together. I thanked everybody for the help.

After a few more hours of descents, and a few falls and moments with the other riders, through switchbacks, some weaving in between tall electrical towers, we would arrive back at the road to Skutz Falls. Tired, wet, our bikes steaming after repeated splashes through muddy puddles, we were all looking forward to getting back to camp. It was 5 o’clock, we’d been riding for eight hours, covered 220 kilometres of off-road and wanted a barbecue dinner. The rain still fell. My left boot felt as though it was filled with water.

Upon returning to camp, Eran and I would have to rescue our tents from a new puddle that had formed under them during the wet day, before tucking into several hotdogs washed down with a beer or two. The stories echoed out into the night as we celebrated having got through the day’s adventures.

The rain continued, but we didn’t care.

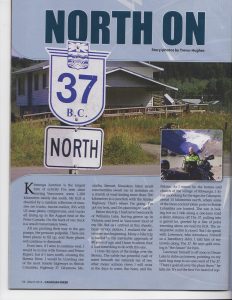

“North on the 37” for Canadian Biker, March 2013 issue

North on The 37

By Trevor Hughes

Kitwanga Junction is the largest hive of activity I’ve seen since leaving Vancouver. My KLR is dwarfed by a random collection of massive ore trucks, tractor trailers, RVs with U.S. state plates, campervans, and trucks all lining up in the August heat at the Petro-Canada. On the back of one truck is a small transmission tower. All are pushing their way to the gas pumps, the pressure palpable. There are fewer places to fill up, and those places will continue to diminish. From here, if I were to continue west, I would be in line with Terrace and Prince Rupert, but if I turn north, crossing the Skeena River, I would be traveling one of the most remote highways in British Columbia, Highway 37. Gityanow, Meziadin, Stewart, Kinaskan, Iskut…small communities await me in isolation on a stretch of road lasting more than 700 kilometres to a junction with the Alaska Highway. That’s where I’m going. I’ve got my tent, and I’m planning to use it.

Before this trip, I had never been north of Williams Lake, having grown up in Victoria and lived in Vancouver most of my life. But as I arrived at this chaotic, hazy service station, I realized the adventure was beginning. Many a bike trip is fuelled by the inevitable approach of 40 years of age, and I have to admit, that it had something to do with this one.

I cross the span of the bridge over the Skeena. The subtle but powerful rush of water beneath me reminds me of two other major salmon rivers I will cross in the days to come, the Nass, and the Stikine. As I weave by the homes and church of the village of Kitwanga, I focus on looking for the signs for Gitanyow, about 15 kilometres north, where some of the most ancient totem poles in British Columbia are located. The sun is baking hot as I ride along a one-lane road a short distance off The 37, pulling into a gravel lot, greeted by a line of poles towering above me and my KLR.

The interpretive centre is closed. But I do speak with Lawrence, who introduces himself as a hereditary elder. I told him of my travels along The 37. He tells me that he believes gold mining is “the future” for him. He himself is off soon to Dease Lake to stake his interest in it, pointing on my tank bag map to an area west of The 37.

“There’s gold all over the place there,” he tells me.

It’s not the first I’ve heard of copper and gold mining near my route. Further north I know of a conflict between the Tahltan First Nation and the British Columbia government about the go-ahead for a big mine. I see a “3 Rivers 1 Future” sticker in Kitwanga Junction, reminding me of the inherent dangers of an open-pit mine near salmon rivers.